Evergreen resident Dan Matus has a piano room. That’s what you have to call the room selected to house his beautiful, shiny grand piano littered with classical sheet music—Bach, Chopin, Rachmaninoff. In the evening hours, he toils over the long keyboard, playing and replaying difficult sections of music, checking tempo, dynamics, emotion. Matus devotes hours a week to the careful study of this piano music, working tirelessly to get the pieces right.

Matus is a well-studied musician. Surrounded by music in his Belizean childhood home, he was always familiar with a piano bench and the black and white keys. Matus recalls piano lessons off and on throughout his childhood, which were never forced, but allowed whenever he expressed interest. In high school, after emigrating to the United States, to Florida, he found music as a point of connection with his new peers; and it was also during these years that he discovered a passion for classical music. “I saw some of my classmates playing—there’s a very specific performance I remember—and it re-piqued my interested in the piano.” Matus thought, “I can do that. I picked it right back up.”

As the math brain and the musical brain so often seem to go hand-in-hand, Matus pursued engineering studies in college but did not devote less time to his musical studies. He continued to work with teachers and practice in any spare moment he could find. When he moved away from his Floridian hometown to pursue a master’s degree in engineering in Minnesota, Matus again doubled-down on his musical education, requesting to take graduate-level music courses on top of his engineering studies, as an elective—a request that was honored after he completed an audition.

Dan Matus has the education, presentation and instrument of a concert-level pianist. And most days, he pounds out these famous masterpieces to an empty room, serenading his daughter, falling asleep in her bed upstairs.

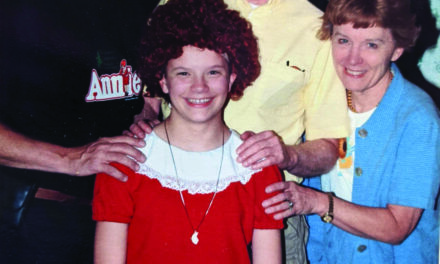

I could relate a bit to Matus’s level of training. From a young age, I was classically trained as a vocalist. Growing up in the church, in tiny schools in a small suburb, there were ample opportunities for musical involvement. My whole life I was placed under the impression that to possess the ability to sing suggested also the responsibility to share said gift; and I was often asked how I planned to use my talents in adulthood. So, I declared a vocal performance minor in college. I continued to sing in churches, in musical theater and for the voice professor whom I only ever disappointed by not being dedicated enough. In fact, it took that let-down for me to realize: I found no pleasure in singing when I was forced to perform. It felt like my relationship with music was twisted, molded to meet some bigger expectation rather than my own understanding of it.

“I have felt guilty for not wanting to perform,” Matus said. Instead, his dedication is due to the pleasure derived from simply doing, without the pressure of living up to a listener’s expectations. “Depending on who’s listening, I never know if [classical] music is appropriate. I have to explain the piece for someone who doesn’t know who the composer is. There isn’t an appreciation for the effort, the details—which is what excites me. I feel obligated to explain… phrasing, melody, soft and loud—and then, ‘Could you play something for us?’ seems like a more complicated ask.”

Somewhere along our evolutionary story, we’ve gotten it into our heads that in the arts—painting, sculpting, music—the process isn’t fully complete until a work is shared. I scoured the internet to confirm this belief and came out with too many annoying quotes to share, all pointing to the incompleteness, or even the bad-ness, of art that hasn’t made it out into the world. And sure, this is the space we expect art to carve out because it increases human connection. But in the age of social media, where you can’t eat a damned avocado toast without feeling the need to tell the world about it, it’s easy to lose sight of the benefit of a private life, including private pleasures. Committing to a hobby is not to half-heartedly set your hands to it; rather there is freedom in diving deep into a practice meant only for your own enjoyment. The need to force boundaries around art on the basis of consumption, public versus private, threatens our relationship with art and what it can do for an artist’s whole health.

“It’s only in the last few years I’ve even called myself a musician,” said Matus, which—when you think about it and consider his years of study, the hours of dedication—is pretty hysterical. Especially when someone else, who knows approximately three guitar chords, can get on a stage somewhere and suddenly be declared a singer-songwriter.

The thing about music is—whether you’re at a concert, as a performer or a listener, if you’re just sitting on your couch spinning records or finding the perfect soundtrack for your hike—it gets in your soul. And no one knows this like Matus, who, five years ago, suffered a major accident while running that rendered his left arm nearly useless.

“It just hung there at my side,” he said. “I had to ponder that I’d wasted so much time not more seriously studying the piano. That I might not be able to play again. And that reignited my desire to play even more and more seriously—which helped me in my recovery. I wanted to do everything I could do for [my injury] to not be ‘the thing’ that kept me from playing at a higher level.”

For Matus, classical piano music is a puzzle, never perfected and infinitely available for studying, deducing, conquering. “It’s about how can I be faithful to the composer? And be as intentional and interesting as possible? Did I capture every slur line? The dynamic markings? I’m fascinated at [the task of] doing this at a high level of musicianship,” he said. When he is playing for others, this “private knowledge” of the music’s complexity is unrealized, and what he senses from an audience is an awkwardness rather than an appreciation. When playing for himself, the work and the complicated beauty of the music can instead be fully explored and expressed. Passions cannot be defined. The music in the soul—or the love of painting, photography, crocheting, whatever makes a person come alive—should be a drive in us that exists with or without an audience.