There is a myth that the design of the stars and stripes of the Betsy Ross U.S. flag, adopted by Congress in 1777, was based on the coat of arms of George Washington. No documentary evidence of this has ever been found, but it is true that the hereditary arms of the Washington family were very important to the man himself, important enough for him to have it painted on his carriage doors in 1790 at a cost of 4 pounds, ten shillings (the U.S. did not convert to dollars until 1792). During his lifetime, it was also applied to his silverware, wax seals, walking sticks, the mantel in the front parlor of Mt. Vernon, and to the livery worn by his servants. It is also true that the flag of the District of Columbia carries identical markings to the Washington coat of arms and that the arms themselves are displayed at the top of every Purple Heart award.

It is often said that “armorial bearings,” to use a proper term, had their origins in battle when leaders became less and less recognizable due to the increase of bodily protection with chain mail, armor and helmets. Coats of arms, as we know them, did not come into general use until the 12-13th centuries, and it’s likely a combination of military needs (identification in battle) and social requirements (identification in tournaments and pageants) conspired to provide a ready market for such a development. Whatever the reason, the practice spread throughout Europe like wildfire. Pageantry was important to great men, men who could afford the expense of the trappings, and arms became a mark of nobility that was rigidly regulated by kings and rulers and passed off to heralds to control, giving rise to the science and art of heraldry. The key component in Western Europe became the hereditary nature of arms. They became intellectual property that was passed from father to son, providing an instant pictorial representation of the lineage and alliances of a particular person that could be easily recognized. In medieval times, few, even those among the nobility, could read and write, so the visual depiction that coats of arms presented found ready use on seals, rings and the like, for signing documents.

The full display of armorial bearings includes the shield, helmet, mantling, wreath, crest, motto, and sometimes supporters. The shield is the only part that is essential to describe the identity of a person. The mantling is an artistic representation of the surcoat that covered a knight’s armor to protect it from sun and rain and which became tattered in battle, while the crest is a representation of what was placed on the helmet to aid recognition. The terminology of heraldry is Norman French, and there are very specific rules as to how the shield may be colored and divided and what may be placed upon it. The description in words of an “achievement,” as a coat of arms can be termed, is called a “blazon.” A design must be unique (differenced), for the infringement of arms owned by another is just as important a legal matter as the infringement of copyright or patents, and there are courts to adjudicate on such matters.

The simple arms of “Azure, a Bend Or” (a blue shield with a diagonal gold band) is one of the oldest in heraldry and was the subject of litigation between the Scrope and Grosvenor families over a period from 1385 to 1389, a case in which several hundred witnesses were brought. The Scropes finally won the right to those particular arms. But how long can you hold a grudge? In 1877, a racehorse owned by a Grosvenor, who was 1st Duke of Westminster, was named “Bend Or” and won the Derby. His son (who became 2nd Duke) had the nickname “Bendor” within family circles. Even today, there is another Bendor in the family: Bendor Gerard Robert Grosvenor, a prominent art historian, dealer and critic.

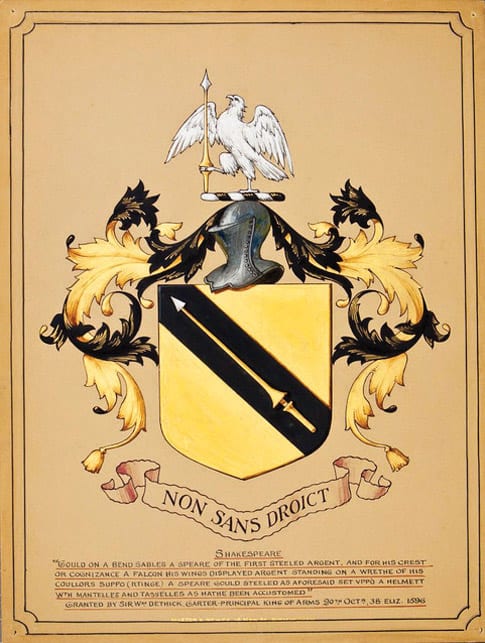

By the 1500s, possession of a coat of arms had become an indication of social class and the cause of much snobbery. John Shakespeare, father of William, had married well and served as alderman, bailiff and chief magistrate of Stratford-upon-Avon, and became mayor in 1568, but his business and standing waned for unknown reasons and his application for a grant of arms was unsuccessful. Son William may have become a well-known playwright and actor, but that calling was very low on the totem pole, however, obtaining arms and thus being classed as a “Gentleman” was important to him. He revived his father’s application and arms were granted. They were “canting arms,” arms that carry in their design some visual pun, in his case, what else but a spear. President Eisenhower’s arms were also canting arms blazoned “Or, an anvil Azure,” an allusion to eisenhauer, German for “iron-hewer” (blacksmith). Note the crest of five stars representing his military rank. The shield blazon for Shakespeare’s arms, granted in 1596, is “Or, on a Bend Sable a spear of the first, steeled Argent” (a gold background with a black diagonal band on which there is a gold spear with a silver tip). Heraldic language is concise and specific, but nevertheless blazons for complete, complex achievements can run to lengthy descriptions. That of the U.S. coat of arms runs to 85 words.

The Washington family traces its roots back to Sir William de Hertburn, who was granted the lordship of Wessyngton in Northern England in the 13th century and adopted the name of the estate. The family was prolific and raised many branches, but because in Britain, a coat of arms belongs to only one person, upon each splintering of a family, the arms must be differenced so that they remain unique, the only overriding exception is that of primogeniture, meaning that the eldest son can inherit the arms of his father upon his death. This is why merely having the same name as a family with arms, but no lineal descent, does not entitle a person to use those arms. Scottish and Irish heraldry differs in this respect; so, too, does Poland, which allows anyone in a family to use that family’s arms without differencing. A woman can claim arms in her own right or a daughter inherit arms in a family lacking a male heir, in which case they are shown not on a shield, but a lozenge (a vertical diamond shape). Those of Baroness Margaret Thatcher, Britain’s first female Prime Minister, are so displayed.

The branch of the family to which George Washington belongs came from Sulgrave Manor in Northamptonshire, England. The original incumbent, Lawrence Washington, received the grant of the present arms in 1592. The shield blazon is: “Argent, two bars Gules, in chief three mullets of the second” (silver, two bars red, at the top three red stars).

Heraldry is alive and well. Not only individuals, but also corporations, institutions, cities, counties and countries all have or want heraldic recognition. Nowadays, any person who can prove they are not a ne’er-do-well and is willing to go through the necessary lengthy protocol can obtain a coat of arms for the sum of $8,778 at the time of writing, which can then legally be the subject of a bequest to their heirs. You can become a ne’er-do-well afterward, without penalty!

© David Cuin 2020