So he had sat all night while her magic needles stung him wasp stings and delicate bee stings. By morning he looked like a man who had fallen into a twenty-color print press and been squeezed out, all bright and picturesque.

—Ray Bradbury, The Illustrated Man

When the freezer-burned remains of Otzi the Iceman melted out of a Tyrolian glacier in 1991, they offered priceless insight into Neolithic habits and habiliment.

In life, Otzi wore a bear fur hat. He wore leggings of goat leather and a sheepskin loincloth. Over his shoulders he draped a heavy coat of hides stitched together with grass twine. Under his clothes he wore 61 tattoos. That makes the art of tattoo at least 5,500 years old, and anthropologists assume it’s a lot older than that.

Virtually every culture on six continents has practiced tattoo. In nearly all cases it’s believed to be derivative of scarification, another universal ancient practice by which one cuts deeply into the skin and then rubs ashes, or minerals, or some other unsanitary substance into the open wound to create a darkened scar. Noting that much of Otzi’s art appears to be associated with areas of chronic ailment, researchers believe it may have served a ritual healing function. In ancient times, tattoos could also denote status, enumerate achievements, invoke cosmic favor, communicate group identity, or simply conform to prevailing ideals of physical beauty. In modern times, tattoos serve the same purposes they always have.

If people seem a bit more, um, baroque than they used to, it’s because they are. For most of the 20th Century, tattoos were considered a vice of criminals, biker gangs and counter-culture agitators. In 1970, maybe 15 percent of Americans had tattoos, and most of those were applied discreetly. Social barriers to dermal embellishment began to fall in the 1980s, as the bolder elements of Gen X embraced punk rock, purple hair, nose rings and deliberate provocation. The current mania for body modification touched off on or about 2005, when “Miami Ink” hit TV screens and teen idols like Justin Bieber and Rihanna started sporting body art out loud and proud. Millennials took to tattoo with a will, and Gen Z is well on its way to becoming the most decorated demographic in history.

“ …Gen Z is well on its way to becoming the most decorated demographic in history.”

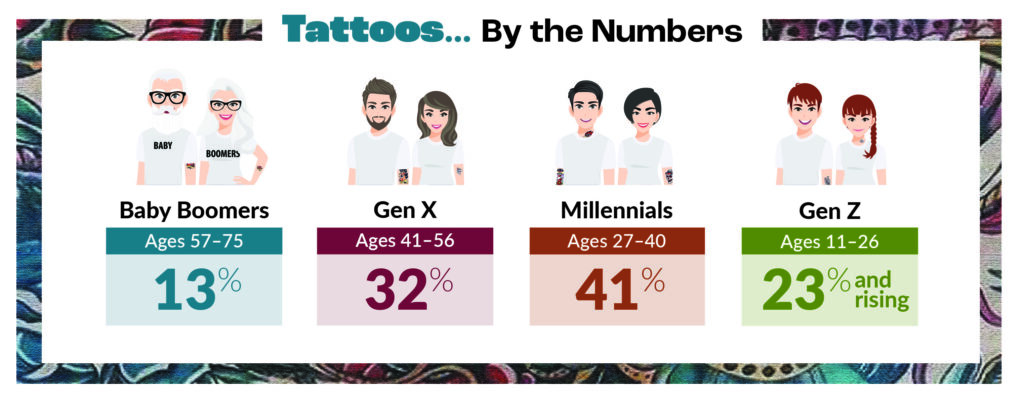

At present, more than 35 percent of Americans of all ages have at least one tattoo, up from 21 percent in 2012. By the numbers, about 13 percent of people between 57 and 75 years old (Boomers) have a tattoo. Of Gen X (41-56 years old), 32 percent have a tattoo, and 41 percent of Millennials (17-42) are thusly adorned. And if only 23 percent of Gen Z (11-26) has as yet gone under the needle, it’s expected that they’ll eventually outstrip all previous generations.

The reasons tattoos have become so popular with the young are many and complex, but fairly predictable. Social media has played a major role, as has the increasing number of stenciled celebrities, which together have effectively normalized body art. Times were, a tattoo could close professional doors. Times are, the stigma of ink, if not erased entirely, is no longer seen as a barrier to success. Perhaps as much as anything, tattoos are embraced as rebellious by generations that have little experience with, or cause for, rebellion.

People under 40 seem to approach tattooing differently than their elders did. As previously demonstrated, they tend to get more of them. According to a survey undertaken by Statista this year, 35 percent of the tatted have just one tat, while 19 percent have 2 or 3, 18 percent have 4 or 5, 16 percent have 6 to 10 tattoos, 9 percent have 11 to 20, and 3 percent have 21 or more. If that sounds like a lot, it may be because Millennials and Gen Zers also seem to be surprisingly casual about permanent personal adornment. Where a geezer might think long and hard before getting a forever stamp, the younger set collects them as breezily as their folks might buy a new tie or another pendant for their charm bracelet. Sociologists studying that phenomenon have found that many among the young see tattoo as a form of self care, a mental therapy to be applied as needed.

Millennials and Zoomers also tend to display their tattoos more prominently (witness the now-ubiquitous “sleeve”), and their deeply personal self-expressive iconography often conforms to standardized themes and meanings, a coded language in which only the Brethren are fluent. Deciding that her generation needed a unifying badge, in 2020, an influential 18-year-old blogger told her tribe to go right out and get a black Z with a horizontal line through the middle tattooed where the whole world could see and celebrate it. Unfortunately, many of her followers did just that, only to discover that their new tat was actually the ancient Germanic wolfsangel, a symbol already busy unifying Neo-Nazi groups around the globe.

What that misbegotten blogger’s subscribers subsequently experienced is called tattoo remorse, a condition shared by about 25 percent of tattooed persons. Interestingly, a survey of the regretful found that 78 percent of those with a single tattoo were sorry they got it, while only 6 percent of people with three felt remorse, and just 2 percent of those with 5 or more were kicking themselves.

Otzi’s thoughts about his intimate gallery died with him, but if he was dissatisfied with his tattoos, there probably wasn’t much he could have done about it. These days, social media feeds and hip urban shoppers are replete with come-ons promising an easy return to the skin you were born with. These invariably lead to more remorse when the painted and penitent discover that tattoo removal isn’t nearly as effortless, affordable or effective as described in brochures.

“Why, they’re beautiful,” I said.

“Oh yes,” said the Illustrated Man. “I’m so proud of my illustrations that I’d like to burn them off.”

—Ray Bradbury, The Illustrated Man