Wyoming native Gail Woodrow was born in Worland, Wyoming on a bitter cold day in February 1913. His mom, Edna, left England and sailed to America for reasons unknown. She trekked her way to Worland via covered wagon, where she fell head-over-heels for tenant farmer Martin, who graduated from Colorado State University with a degree in agriculture. Born and raised in Longmont, Colorado, it’s anyone’s guess how Martin became a tenant sugar beet farmer in Worland.

Holding the position of third eldest son of 11 children, Gail seemingly thrived throughout his childhood; quite a feat considering he walked daily to school in unrelenting blizzards that consisted of an uphill climb going both to and from the one-room schoolhouse. “My mom was a terrible cook,” Gail often lamented. “Our lunches never wavered from a biscuits and gravy cuisine that was obviously frozen and never thawed throughout the school day.”

Seven days a week, Gail and his siblings were tasked to feed the livestock, milk the dairy cows, feed hundreds of turkeys, and a few “old nags” named Dan and Nig, as well as “Old Blind Dick,” that came with the farm and were tasked to pull the sugar beet wagons. Despite the hard work, Gail bonded deeply with the farm’s critters, especially Old Blind Dick. He once recounted, “I rode Dick daily, without a bridle and saddle, and taught him how to turn right, left, stop, or charge to a run and come to a gentle stop without the aid of a bit.” Gail was an early pioneer of natural horsemanship, working with horses based on natural instincts and methods of communication, with the understanding that horses do not learn through fear or pain, but rather from pressure and the release of pressure.

Gail sang like Enrico Caruso, one of the first major singing talents to be commercially recorded from 1902 to 1920. Wyoming hosted a statewide singing contest, which Gail won. The guy who took second went on to perform on Broadway. Gail, somewhat insecure and overwhelmingly humble, never sang beyond the shower, but to his daughter’s delight, he sang “My Pony Boy” ad nauseam: Pony boy, pony boy, won’t you be my pony boy? Don’t say no, here we go, off across the plain… Giddy up, giddy up, giddy up, whoa! My pony boy.

Gail’s daughter was born with developmental dysplasia, a condition when the ball and socket joint of the hip does not properly form. Plagued to wear braces that forced her legs to jut out sideways, Gail found a soft pillow-horse that provided a reprieve from the braces. Her legs remained splayed as her chest rested against the neck of the pillow-horse to hold the babe erect. With hips and joints aligned three years later, the soothing horse pillow and her dad’s affection for horses inflicted her with horse fever, much to the chagrin of her mother, who feared horses as well as dogs, for deeply hidden secrets that were revealed days before her death.

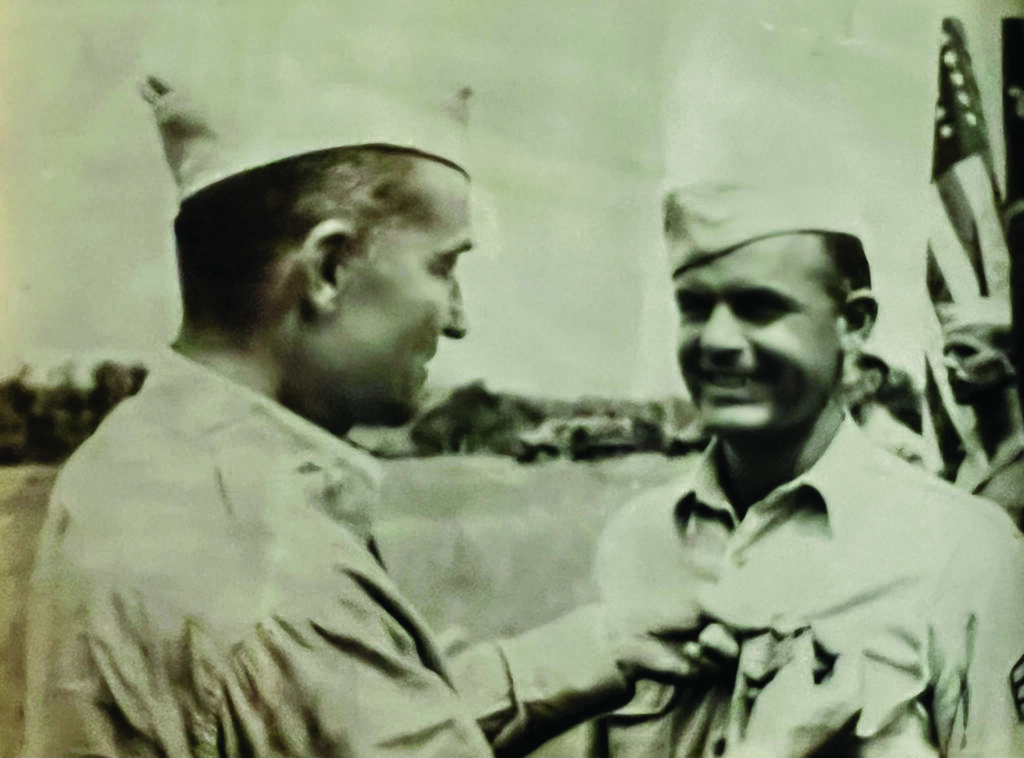

Attending the University of Wyoming for two years, coeds constantly pursued Gail because of his suave looks and gentile singing. He worked as a valet at the Tri Delta Sorority, where he met Lucille, the fourth eldest of 13 kids, who was quite painfully shy. The U.S. Army drafted Gail to a four-year stint, giving Lucille plenty of time to plan how she’d snag the much sought-after hunk.

Care packages from an array of women found their way to Gail, who claimed, “Girls loved the idea of sending food to me, but none of their packages remained intact with the exception of Lucille’s. Nary a crumb crumbled. I never recalled her face, much less speaking to her, but it was her culinary talents that attracted me.” Lucille, unaware that her baked goods and tidy packaging rated tops with Gail, convinced a girlfriend to move from Laramie to Los Angeles so they would be the first of Gail’s admirers to meet his homebound ship. Less than a month after Gail’s arrival, they said their “I dos.”

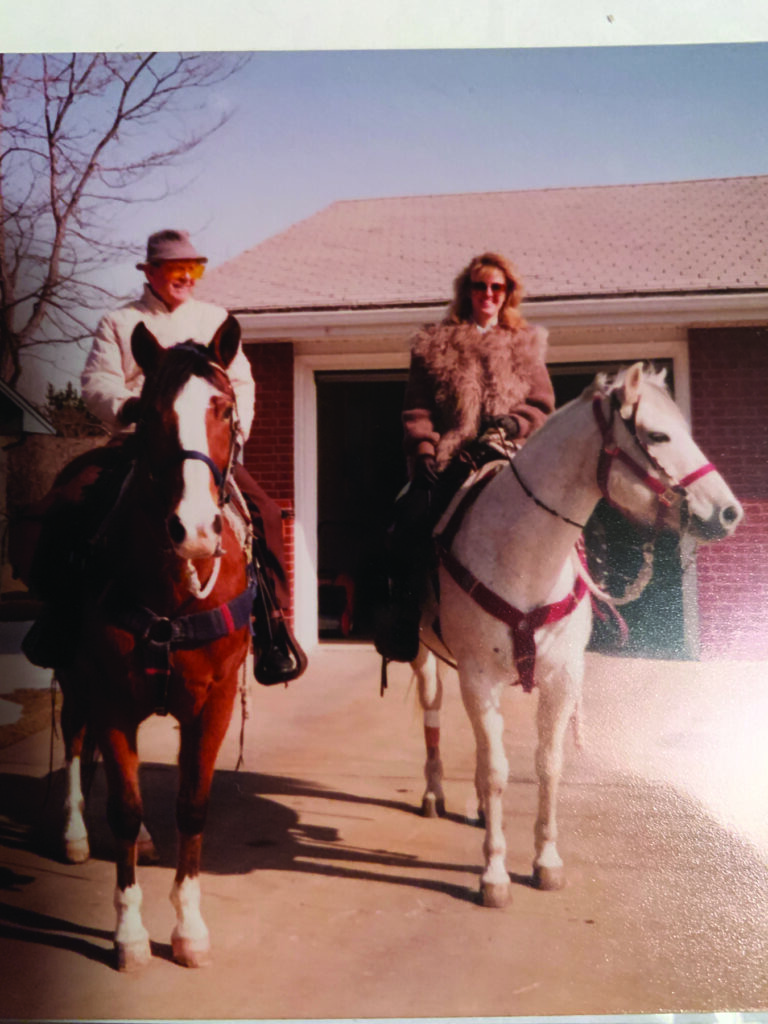

The GI Bill enabled Gail to complete his college degree from the American University in Washington, D.C. He worked briefly for the State of Wyoming. Gail’s sister, Hazel, married to Joe, then Treasurer of CSU, told Gail, “There’s a job for you with the Department of Agriculture.” Gail claimed his 33 years working at CSU overseeing grants and funding for the land grant colleges was “pure joy.” He became best friends with Nick Booth, who was working on his PhD, and later became Dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Science from 1966 to 1977. Dr. Booth ensured Gail’s horse-crazy daughter was given the horse she had pined for since birth. Gail also considered Dr. John Matsushima—who was the son of Japanese immigrants and raised on a family farm in Platteville, Colorado—a “best friend.” The two often worked as a team during the National Western Stock Show, allowing Gail’s daughter, then in elementary school, to tag along.

A born storyteller, Gail’s daughter never tired of hearing his stories. All were her favorite, including this tale: “Our farm was infested with prairie dogs, which I caught and tamed. Living in a house with a sod floor, my mother never complained when I caught and tamed them. Their chatter constantly amused me, and I learned prairie dogs could both chuckle and laugh, and if distressed, they screamed. They loved to sit on my head and chatter away while I did my chores.”

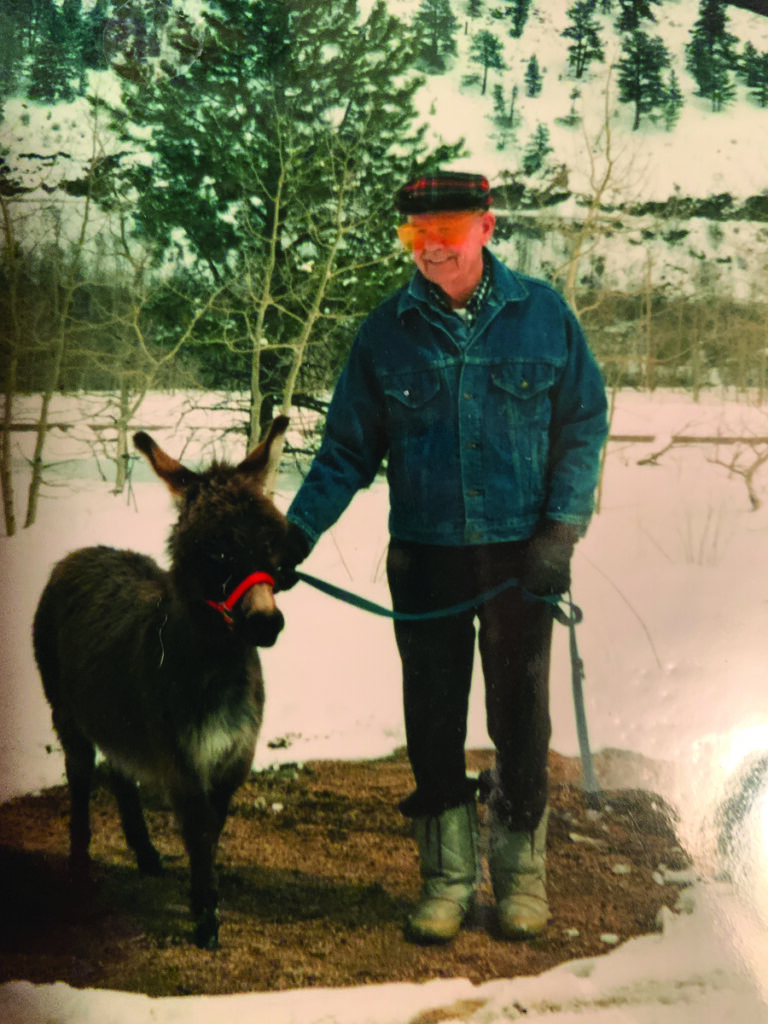

In his mid ’80s, Alzheimer’s robbed Gail’s mind of its once sharp acuity, and bone cancer wasted away his body. This, Lucille could not handle, so Gail lived with his daughter, who moved to Evergreen in 1985. Basking in the company of his daughter’s horse and miniature donkey, and fishing at Evergreen Lake remain treasured memories for her. His daughter worked at Seniors’ Resource Center’s Yellow House in Evergreen, no longer a thing, and this enabled Gail to participate in their Daybreak Program. He loved the ongoing activities, and thought it was a daily job. He often quipped, “That Yellow House keeps me busy from the moment I arrive until I leave, but when do I get a paycheck?”

As his health declined, Gail was accepted into Hospice of Saint John in Lakewood, founded by Father Paul von Lobkowitz. Gail’s daughter was a devoted volunteer there. Father Paul welcomed the plethora of animals Gail adored, including the horse, donkey and Golden Retriever mix, Max. Father Paul loved on them all and often claimed, “I would rather die in a kennel or barn surrounded by animals than die in a flower garden, if given the choice.”

It’s not often a daughter can pay tribute to the character of her father. “My dad was my role model, my best friend and my hero. There’s never a moment when I’m with my horse or walking my dogs that I don’t think of him. I will forever treasure the gift of time I had to care for him as his life ebbed away. He loved Evergreen as much as I, especially picnicking at Evergreen Lake, standing together on the boardwalk, and recanting countless memories of being in the company of horses. Every moment spent with my dad remains a precious memory, which peaks in the month of February. He often claimed I was the best birthday present he ever received, and I know he was mine. Happy heavenly birthday, Dad!”